Image & Violence

The vlog dives into themes of trauma, gender agency, and political violence through powerful storytelling and documentary film analysis.

Week 1 Blog Entry: How Does Violence Function in The Train of Pain?

Violence, especially political violence, is a layered and visceral experience that disrupts bodies, lives, and communities. It cannot be reduced to cold facts or distant images. In Killer Images (2012), Ten Brink and Oppenheimer stress that representing violence in film demands a “politics of the visceral,” blending ethical concerns with the affective experience of witnessing violence (p. 4). This approach challenges filmmakers to consider how violence is not only seen but felt.

My short documentary The Train of Pain embodies this complexity by using found footage and archival materials depict the Soviet deportations experienced by my grandmother and many others. The film resists traditional historical narratives, instead offering an experiential portrayal of violence as intimate and ongoing rather than distant or spectacular. As Ten Brink and Oppenheimer argue, film “gives form to violence” and “shapes the way we experience violence” (2012, p. 6).

Violence in The Train of Pain appears as a blend of human and non-human elements: the freezing train compartments, the cold bureaucracy ordering deportations, and the emotional scars visible on survivors’ faces. This approach draws viewers into the embodied reality of political violence, highlighting how victims, perpetrators, and witnesses each experience violence differently (p. 8).

This representation contrasts with mainstream media coverage, which often sensationalizes or abstracts violence. Fallon (2016) describes war documentaries as operating with a “double-optic”: combining aesthetic engagement with critical reflection on conflict narratives. Our film adopts this double-optic, inviting empathy for overlooked personal histories and confronting violence as a lived reality.

By working exclusively with archival and found footage, the project embraces alternative documentary practices that highlight both the power and the limitations of historical evidence. This project is an ethical as well as aesthetic endeavor — a commitment to stories marginalized or silenced.

Week 2 Blog Entry: Gender, Violence, and Gulistan: Land of Roses

This week's examination of gender and political violence, as presented in Gulistan: Land of Roses, interrogates conventional war narratives that frequently marginalise or stereotype women's experiences. The film focusses on female PKK insurgents combating ISIS in Kurdistan, providing a vital alternate viewpoint that emphasises women's agency in violent conflict, therefore challenging the conventional male-centric narrative of war.

Gulistan employs intimate observational cinematography that immerses the audience in the combatants' quotidian experiences. Close-ups in interviews convey emotional authenticity and personal subjectivity, while natural lighting and handheld shots produce a raw, unrefined look that eschews sensationalism. The documentary intertwines introspection, narrative, and companionship with armed warfare, merging the emotional and political dimensions. This stylistic decision associates Gulistan with alternative documentary traditions, emphasising marginalised voices and challenging conventional victim/perpetrator dichotomies (Gentry & Sjoberg, 2015).

The video distinctly prioritises women's voices—via their testimonies and direct addresses—thereby humanising these soldiers and emphasising their ideological reasons and battles. This challenges simplistic "mother/whore/monster" tropes sometimes assigned to women's violence, depicting the fighters as multifaceted, autonomous political agents rather than dehumanised caricatures (Gentry & Sjoberg, 2015).

The film aligns with UN Resolution 1325, which underscores the necessity of gender integration in peace and conflict processes, recognising the influence of gender on experiences and repercussions of violence (UN Women, 2000). Gulistan conforms to this concept by depicting women as active participants in continuing conflicts, hence contesting passive victim narratives (Trisko Darden et al., 2019).

In my project, Gulistan advocates for an experimental methodology regarding voice and perspective. The objective is to highlight marginalised narratives and contest prevailing discourses through formal experimentation—intimacy, pacing, and the prioritisation of testimonials—to enhance audience involvement and confound reductive interpretations of conflict and gender.

Helvetica Light is an easy-to-read font, with tall and narrow letters, that works well on almost every site.

This week's emphasis on montage as a transformative method of reconfiguration strongly corresponds with Frantz Fanon's "Concerning Violence" and the documentary "Concerning VIOLENCE." Fanon's work elucidates violence as a complex political force, necessitating participation that beyond mere depiction. It is not only an event but a process interwoven with colonialism, resistance, and decolonisation (Fanon, 1963). In Concerning VIOLENCE, montage interrupts linear historical narratives by fragmenting and recontextualising archive material. This approach aims to reveal the persistent character of colonial violence—cultural, existential, and systemic—while contesting sanitised or propagandistic media representations. Fanon's work functions as a philosophical montage, integrating theory and firsthand accounts to stimulate novel forms of political awareness.

Jamie Baron’s notion of the “archive effect” (2012) is essential; found footage films such as Concerning VIOLENCE illuminate the mediated and created essence of archival images, prompting viewers to scrutinise their authority and ideological foundations. The archival material evolves from passive evidence into dynamic arenas of contestation and resistance. "The Train of Pain" raws upon these tactics. We are exploring non-linear editing and the juxtaposition of diverse pictures and sounds to generate tension and novel meanings. This montage technique enables us to emphasise violence as a contentious political reality rather than mere spectacle, reflecting Week 1’s emphasis on emotive experience. In the current media-saturated landscape, critical engagement with archive appropriation is imperative. It promotes contemplation on the narration and remembrance of violent past, highlighting the necessity of elevating marginalised viewpoints and challenging prevailing narratives.

Week 3 Blog Entry: Montage, Fanon, and the Politics of Violence in Found Footage Film

Week 4 Blog Entry: Citizen Filmmaking and the Visual Politics of the Arab Spring

The Arab Spring upheavals commencing in 2010 transformed not just political regimes but also the production and dissemination of images depicting political violence and resistance. The emergence of citizen filmmaking significantly disrupted conventional documentary styles, establishing a novel visual lexicon characterised by immediacy, fragmentation, and community authorship.

Peter Snowdon’s The People Are Not an Image (2021) contends that these vernacular videos transcend mere event documentation, functioning as dynamic, emotive activities integrated into the rhythms of protest. They oppose explanatory frameworks, instead encapsulating transient “forms-of-life” that express presence and urgency through fragmented glimpses. Snowdon's notion of the anarchive—a non-hierarchical, ever updating collective archive—subverts traditional notions of authorship, framing citizen videos as moral rather than legal assets of the revolution (Snowdon, 2021). This communal ownership converts filmmaking into a political act of defiance and unity.

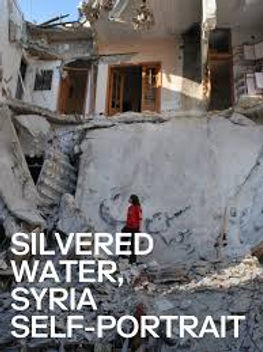

Mohammed Malas's Silvered Water: Syria Self-Portrait (2014) exemplifies these ideas by merging archival material and personal recordings from the besieged city of Homs. The film addresses necropolitics by emphasising life's endurance in the face of violence, merging realism, poetry, and the "marvellous" to challenge simplistic victim narratives. This multifaceted emotional experience closely parallels the disjointed essence of citizen filmmaking, encouraging spectators to observe resilience in conjunction with misery.

For the "Train of pain" project, these ideas motivate an experimental methodology that incorporates fragmentation, anonymity, and communal narrative construction. Our objective is to contrast images of violence with quotidian instances of resistance and community, fostering a conversation between visibility and invisibility, existence and demise. This tactic enhances the montage and archive appropriation techniques from Week 3, intensifying the critical examination of how pictures mediate political violence and memory.

Week 8 Blog Entry: Aftermath and the Aesthetic of Absence in Documentary Practice

This week's emphasis on aftermath photography and its connection to documentary film provided essential avenues for engaging with photographs that address violence not in its immediate occurrence but via its enduring reverberations. Films such as Ognjen Glanović’s Depth Two and Esther Perel’s Toponimia illustrate how landscapes retain and convey histories of pain long after the cessation of violence.

Jo Ratcliffe's notion of aftermath photography examines the "landscape as pathology," wherein trauma is expressed both metaphorically and forensically (Ratcliffe, 2015). This significantly shaped our methodology, leading us to investigate environments that seem ordinary but are infused with both overt and latent histories of violence. Our objective was to engage viewers in a forensic spectatorship that highlights absence as much as presence.

Depth Two examines mass graves and disputed memories through a deliberate, understated approach, tracing a historical pedigree from Roger Fenton's Crimean War photographs to Paul Seawright's Hidden (2003) (Ferrandiz et al., 2017). This reflects Alfred North Whitehead's aesthetics, viewing the perception of lived experience (Whitehead, 1929) as violence inscribed on the landscape rather than recounted.

Our documentary employs a comparable five-stage narrative framework, transitioning from expansive dismal imagery to intimate remnants and historical content, concluding in a symbolic act of healing. By abstaining from the portrayal of graphic violence, we participate in Ratcliffe’s “regime of absence,” prompting profound contemplation reminiscent of Claude Lanzmann’s Shoah (1985).

This aesthetic of absence shapes our understanding of 'alternative' practice—emphasizing contemplation and nuance rather than sensationalism, honouring absence while remaining observant. These decisions influence our editing and sound design, promoting critical engagement and discourse on memory, erasure, and justice.

Week 5 Blog Entry: The Interview as Alternative Documentary Practice

This week's emphasis on the documentary interview has enhanced my comprehension of how interviews operate not merely as instruments for exposition but as intricate cinematic constructs that mediate truth, subjectivity, and power dynamics.The project concise documentary intentionally employs a reflexive interview methodology influenced by Errol Morris, emphasising both the filmmaker and the interviewee, thereby questioning conventional impartiality.

According to Leger Grindon (2007), interviews seldom serve as impartial verbal accounts; instead, significance arises from framing, camera angles, and editing in addition to the spoken word (Grindon, 2007, p. 334). This revelation prompted me to explore camera placement and illumination that highlight vulnerability while rendering the filmmaker's presence apparent, thereby subverting the traditional "fly-on-the-wall" approach.

The approach adheres to alternative documentary traditions that eschew sanitised, authoritative narratives. Inspired by French cinéma vérité, we accept uncertainty and contradiction, akin to Rouch and Morin’s Chronicle of a Summer (1960), where openness and doubt are essential to political involvement (Nichols, 2017). By employing non-linear editing and intervals of silence, we encourage viewers to critically engage with subjectivity instead of passively consuming a refined narrative.

In contrast to American political films, like Emile de Antonio’s analytical interview structure, our methodology emphasises performativity and regards the interview as a contested arena rather than a mere conduit for information (Grindon, 2007). Historically, interviews have progressed from Grierson’s initial documentaries to contemporary digital media, illustrating changing power dynamics. The projects endeavour reclaims this domain for marginalised voices by upholding collaborative authorship and resists the reduction of interviewees to simple sources (Nichols, 2017).

Drawing from Morris's Interrotron approach, we utilise direct gaze interviews to elicit active spectator participation (Morris, 2016). Our sound design contrasts interviews with ambient and historical music, enhancing emotive textures and challenging the relationship between image and testimony—reflecting findings from Week 5’s seminar.

In summary, our approach critically examines the formal and ideological aspects of documentary interviews, contributing to alternative techniques that strengthen marginalised viewpoints. Future endeavours will further polyvocality and continue to explore form, maintaining attentiveness to political and ethical issues.

Week 9 Blog Entry: The Double Loyalty of Reenactment and the Mediation of Trauma

This week's emphasis on reenactment in documentary created a contradictory realm between history and representation, as well This memory and imagination. Bill Nichols's notion of reenactment's "double loyalty" underscores this tension: reenactments must be acknowledged as both representations of historical events and as apart from actual reality (Nichols, 2008, p. 73). This dual desire engenders an eerie recurrence of what is historically singular (Nichols, 2008, p. 75).

The involvement in reenactment was influenced by The Missing Picture (Rithy Panh, 2013) and Ghost Hunting (Raed Andoni, 2017), films that employ reenactment to explore the challenge of completely recovering traumatic histories. In The Missing Picture, Panh’s clay figures symbolically restore obliterated histories, converting “earth as memory” to counter the Khmer Rouge’s visual obliteration (Panh, 2013). Nichols emphasises that reenactments facilitate the past through “imaginative investment, projection, and creation” instead of providing documentary evidence (Nichols, 2008).

Ghost Hunting similarly reenacts the anguish of confinement with survivors, acknowledging the challenge of conveying suffering without collective acknowledgement. These methodologies influenced our project's reenactment strategy as a symbolic production rather than a literal replication, acknowledging the elusiveness of trauma and eliciting affective reality through stylised performance.

The five-stage narrative of our film encapsulates this tension:

1. Disjointed recollections

2. Stylised reenactments indicating performance

3. Contextualisation of Archival Material

4. Silence accentuating the inexpressible

5. Symbolic gestures indicative of healing or persistent struggle

This emphasis on the mediation of reenactment encourages viewers to explore authentic and enacted memories. Within the realm of alternative documentary, reenactment serves as a potent ethical practice—questioning openness and embracing the lyrical expression of pain. We intend to persist in our experimentation with shape, according to Nichols's concept of reenactment as a "new object" that generates "new pleasure" (Nichols, 2008).

Bibliography

Fallon, K. (2016). Why We (Shouldn't) Fight: The Double‐Optic of the War Documentary. In D. Cunningham & J. Nelson (Eds.), A Companion to the War Film.

Ten Brink, J., & Oppenheimer, J. (2012). Killer Images. London: Wallflower Press.

Gentry, C., & Sjoberg, L. (2015). Beyond Mothers, Monsters, Whores: Thinking about Women's Violence in Global Politics. London: Zed Books.

Trisko Darden, J., Henshaw, A., & Szekely, O. (2019). Insurgent Women: Female Combatants in Civil Wars (Chapter 2).

UN Women. (2000). UN Security Council Resolution 1325 on Women, Peace, and Security. United Nations.

Fanon, F. (1963). Concerning Violence. In The Wretched of the Earth. New York: Grove Press.

Baron, J. (2012). The Archive Effect: Found Footage and the Audiovisual Experience of History (extracts).

Snowdon, P. (2021). The People Are Not an Image: Vernacular Video After the Arab Spring. London: Verso.

Malas, M. (Director). (2014). Silvered Water: Syria Self-Portrait [Film].

Grindon, L. (2007). Q & A: Poetics of the Documentary Film Interview. Project Muse.

Morris, E. (2016). Who’s Asking? Film Comment.

Nichols, B. (2017). Introduction to Documentary (3rd ed.). Indiana University Press.

Ferrandiz, C., Robben, A. C. G. M., & Wilson, S. (2017). Sites of Violence and Memory: Mass Graves and Forensic Practices.

Ratcliffe, J. (2015). Trauma and Landscape: Manifestations of Pathology in the Contemporary Image. Journal of Visual Culture, 14(3), 419–433.

Whitehead, A. N. (1929). Process and Reality.

Dimitrijević, B. (2018). Narrative Movements in Depth Two. Film Criticism Journal.

Szczepan, L. (n.d.). Landscapes of Postmemory. rcin.org.pl

Nichols, B. (2008). Documentary Reenactment and the Fantasmatic Subject. Critical Inquiry, 35(1), 72-89.

Panh, R. (2013). The Missing Picture [Film].

Andoni, R. (2017). Ghost Hunting [Film].

Images

fv_web_themissingpicture_header_1920x847.jpg : The Missing Picture | Wexner Center for the Arts:Available at:https://wexarts.org/film-video/missing-picture-0(accessed. 01/08/2025)

depth-two_main-still_4-1536x830.jpg.Available at: https://mubi.com/en/tr/films/depth-two : (Accessed 01/08/2025)

Depth Two (2016) - IMDb: Available at: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt5354986/ :(accessed 01/08/2025)

Silvered Water, Syria Self-Portrait (2014) | MUBI: Available at: https://mubi.com/en/tr/films/silvered-water-syria-self-portrait

p10841312_v_h9_aa.jpg:Concerning Violence | Rotten Tomatoes: Available at:https://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/concerning_violence(accessed. 01/08/2025)

Prime Video: Gulîstan, Land of Roses Available at https://www.primevideo.com/-/tr/detail/Gul%C3%AEstan-Land-of-Roses/0Q7I1YU9I0RBXBEEKSHJ99DZB5 (Accessed 01/08/2025)

GulistanLandOfRoses3.jpg Available at: https://www.cinemapolitica.org/film/gulistan-land-of-roses/(Accessed 01/08/2025)

Oppenheimer_01.jpg Available at: https://film-grab.com/2023/12/06/oppenheimer/(accessed. 01/08/2025)

Before Russia deported Ukrainians, Soviets abducted Baltic citizens - The Washington Post: Available at:https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2022/04/02/russia-deportation-ukraine-baltics/(accessed. 01/08/2025)